Source >>>

Increasingly, countries are using Climate Change Gender Action Plans (ccGAPs) to identify gender-specific opportunities in nationally-determined climate-related priority sectors through a participatory, multi-stakeholder process – and establish blueprints for action.

Laura Cooper Hall and Ana Rojas

Photo: Photo credits: Shutterstock

So how do ccGAPs support countries to establish gender-responsive blueprints for climate action? At the global level, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) began recognising the link between gender and climate in 2001 with Decision 36/CP.7, which focused on formally addressing representation and participation of women. This has evolved into the agreement on a five-year Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender (LWPG) and its gender action plan (Decision 3/CP.25), agreed upon at the 25th Conference of Parties (COP25) of the UNFCCC in 2019. Furthermore, the UNFCCC Paris Agreement and its implementation guidelines recognise gender equality and women’s empowerment as guiding principles for climate action.

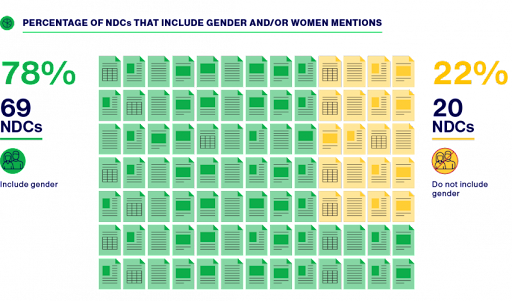

A recent report from IUCN, Gender and national climate planning: Gender integration in the revised Nationally Determined Contributions, provided insights on how gender inclusion in climate policy has grown through revised nationally-defined climate action plans under the UNFCCC Paris Agreement and its implementation guidelines. The research showed that countries around the world increasingly recognise women as vital stakeholders and agents of change in advancing urgent climate action.

Photo: Photo credits: Estudio Relativo for IUCN

Photo: Photo credits: Estudio Relativo for IUCN

Furthermore, the international community is increasingly moving towards identifying methodologies and support for ensuring NDC implementation integrates gender equality considerations. For example, the NDC Partnership’s Practical Guide Developing Gender-responsive NCD Action Plans provides an overarching framework for integrating gender considerations in national climate change planning and investment opportunities.

Similarly, countries are increasingly using IUCN’s ccGAP methodology to chart national ambitions for gender-responsive climate solutions that align with their NDCs. By relying on national policy context analysis and mutual capacity building amongst national women’s organisations, gender experts and climate change decision-makers and practitioners, the ccGAP methodology supports the identification of gender gaps and opportunities that enable the co-creation of gender-responsive activities that align with and enhance the country’s priorities for climate action.

ccGAPs as tools for implementing gender-responsive NDCs

Pakistan, Ecuador and Guatemala are adjusting the ccGAP methodology to address their contextual needs and country-driven climate actions.

Pakistan’s experience shows how collaborative engagement within national climate frameworks can result in thorough, practical and gender-responsive plans for climate action. With implementation support from IUCN, the Government of Pakistan’s Ministry of Climate Change (MoCC) is developing a ccGAP to ensure that cross-sector climate action meets the needs and priorities of the people of Pakistan through Readiness Support from the Green Climate Fund (GCF).The Pakistan ccGAP development included a comparative analysis of the activities identified in its updated NDC, its National Climate Change Policy and the sectoral ccGAP action plans. The analysis supports the MoCC in developing a national project pipeline strategy which will result in gender priorities being mainstreamed across existing MoCC projects. The Pakistan ccGAP also adopted COVID-19 precautions by harnessing virtual workshops, engaging women’s groups and representatives to gather inputs on national climate policy priorities.

In Ecuador, IUCN and the Ecuadorian government’s National Council for Gender Equality are supporting a ccGAP process financed by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development’s ARAUCLIMA initiative. The ccGAP development is being led by the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition via the Sub-Secretary of Climate Change and it prioritises the same 11 sectors that are identified in Ecuador’s NDC. Here, the ccGAP process differs slightly from others, building upon the adaptable nature of the methodology. The Ecuador ccGAP mapped existing projects underway throughout the country, establishing a knowledge base of where areas of immediate national opportunities for gender integration may be. Complemented by the sectoral action plans generated through workshops that include diverse representatives from community and local levels, this mapping will help design the ccGAP to contribute to coherent implementation of the across national climate plans and programmes.

In Guatemala, the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources is also working with IUCN to develop a ccGAP. Here, direct collaboration with Guatemala’s NDC focal point, the team tasked with managing their NDC process, ensures the ccGAP’s alignment with the country’s NDC. Funded by the United States Agency for International Development under its partnership with IUCN on Advancing Gender in the Environment (AGENT), Guatemala’s ccGAP process will also include a mapping of existing government initiatives that will support the design of the nationally-specific action plans. Building in funding for priority implementation activities that are supported by the mappings, Guatemala’s ccGAP further demonstrates adaptability to support stakeholder priorities. The ccGAP will also prioritise intersectionality by including young people, indigenous peoples and other groups to ensure diverse women’s priorities are key considerations in shaping gender-responsive climate actions.

An opportunity for moving commitments towards action

The ccGAP processes implemented in Pakistan, Ecuador and Guatemala demonstrate the diverse ways in which countries can use this method to ensure gender-responsive climate action, and adapt the method to create coherent plans across national climate priorities and commitments. As Parties reflect on their implementation of the activities included in the UNFCCC’s Enhanced LWPG, ccGAPs offer insights on how countries are inclusively moving from global commitments to action.

This blog is by Laura Cooper Hall and Ana Rojas. It also appears on the NDC Partnership’s website.